A Small Act with A Lot of Impact

A Look at Danny Rojas and Nick Saban

If you read my last post, I mentioned a childhood dream of mine, to be the next great Florida Gator quarterback. That dream never came to fruition, but when I was in college I had the opportunity to be a part of a fantastic team and culture, the Sprint Football Team.

Not Spring Football—we play our games in the fall.

And to answer the other questions that often come when I bring up the team: All the rules are normal college football rules—we wear pads, we play full tackle, there are 11 people on the field for each team, and a touchdown is still six points with an extra point for 1. The two differences are that there are no replays to fix mistakes in referee calls, and the entire team (every position) weighed in at the same allowed weight two days before every game. When I played, the weight was 172 pounds, and it has since increased to 178 pounds. Think wrestling meets football except, that because the weigh ins are a few days before games that allows for adequate rehydration and fueling, some people are coming into the game 10-20% heavier than they were for weigh ins.

Football is a top tier mechanism for teaching toughness and teamwork, and through Sprint Football, I became friends with some of the best humans I have ever met. The following is a story of forgiveness, grace, and genuine friendship. It is an embarrassing story for me, but because of this, it highlights another’s leadership.

At the end of my junior season, we were set to showdown with Army in West Point as both undefeated teams. Part of the brainwashing of the Naval Academy is to see any Army-Navy competition as the apex of all society. We sing the Blue and Gold after every single function at school, and at the finale we are supposed to all shout “Beat Army.” We do this after talks from the wide range of mandatory lectures we attend. We do it after every single sporting event, even after we play Ohio State or Air Force.

That year, some folks from ESPN had showed up to a game of ours to film a promotional video for our Sprint Football game against Army. While, for us as players, this was a huge deal, it was such a non-factor that the only evidence that I can find that this promotional video ever even existed is this.

It aired the morning of our game, and our entire team gathered into the hotel bar to watch it. Like many of these types of videos, it was cheesy—showing our team captain and one of Army’s players saluting dramatically in their game uniforms. It was the closest I was ever going to get to my Florida Gator dreams of being a hero on ESPN. I don’t recall being in a single second of video which is all for the best because it would make the rest of this story even more embarrassing for me.

If you are catching what I am putting down, the game did not go well. In fact, it went atrociously. Although the scoreboard didn’t say blowout, it was possibly one of the worst outings of a player in the history of athletics. Without looking at the stats of a game eleven years ago, I can tell you that I completed more passes to the opponents than I did to my teammates, and I had a fumble for good measure. The entire game the opponent’s defense was relentless, and it became somewhat of an outer body experience, as I watched myself be so helpless and useless to my teammates.

At the end of the game, when the clock finally had the grace to count down to zero and release me to my shame, I broke down on the field sobbing. My parents were in the stands, but I stood on the field alone crying as much as I have ever in my life. Ironically—this may have been the closest I got to emulating a Florida great for his public crying, but there was no rousing speech from me in the end. No one came to comfort me, except for one coach who held me like his son and let me continue to cry.

It was a game that no one cared about in a sport that no one cares about, but that didn’t seem true. The team cared. My teammates cared. My coaches cared. And I had failed all of them epically.

A few months later, it was the middle of what we called the Dark Ages, the school weeks between Christmas break and Spring break in which Annapolis is cold, wet, and dreary. I was in my own Dark Ages because I was still carrying around the burden of having let all my closest friends down.

Most of it was probably in my 20-year-old brain, but it felt like everyone was avoiding me. When we’d first come back from West Point, friends and people in the hallway would ask how the game went. I couldn’t give them an answer because I was so embarrassed. Eventually people stopped asking. I ostracized myself from my teammates because I was so ashamed. Our seniors were graduating, and they found out what their first assignment in the Navy would be, but I didn’t think they’d want me around for the celebrations. People that know me as a social being will see that this was the worst form of torture. I would find myself groaning in my chair as a certain play from the game would play back in my head. I was angry at the coaches for the play calling, and I was angry at everyone else for no good reason.

Again, you might be wondering—it was the Sprint Football Army Navy game, right? It’s not like it was actually that big of a deal. For me though, it was. I didn’t care that no one came to the games—football was my one and only passion. I lived and breathed the game. Football was life. As my first year starting, it had been chance to put the endless hours of my life I had dedicated to the game to make shit happen. Of course, the score of that game didn’t matter, but it took the grace of another person to help me see that.

One cold February evening, a teammate stopped by my room. He was an absolute stud of a human being. Raised in a cattle farming family in Missouri, he was tough, smart, gritty, and a helluva defensive end. For his talent and attitude, he was one of the top leaders of the team. He was exactly the person I felt I had let down the last Fall.

He stopped by the room to talk about our training plan for an upcoming physical test at school. I don’t remember the conversation, but I remember what he left me with. We finished the conversation, and I immediately put my headphones on and turned back towards my desk, assuming he was leaving.

Suddenly, I felt him wrapping his arms around my chair back and my chest to hug me. He hugged me tight, like he didn’t care about the last game, like he was my friend, like someone who cared about me. The thing is, I know he was mad about that game, but, in that hug, he showed me the grace and forgiveness I couldn’t give myself. In a moment of selfless leadership, he put aside his own feelings and showed that he cared more about me as a friend than as a teammate. His caring helped bring me out of that spiral of wallowing self-pity, and it helped me see what the Sprint Football team was truly about. Sure beating Army was great—which we did the next year—but it was more about being in fellowship with great people. It was about working together as a team towards a common, fulfilling goal and meeting adversity head on in pursuit of that goal. It was about having a community of boys with which we could head into a storm with, get crushed by the storm, and try again.

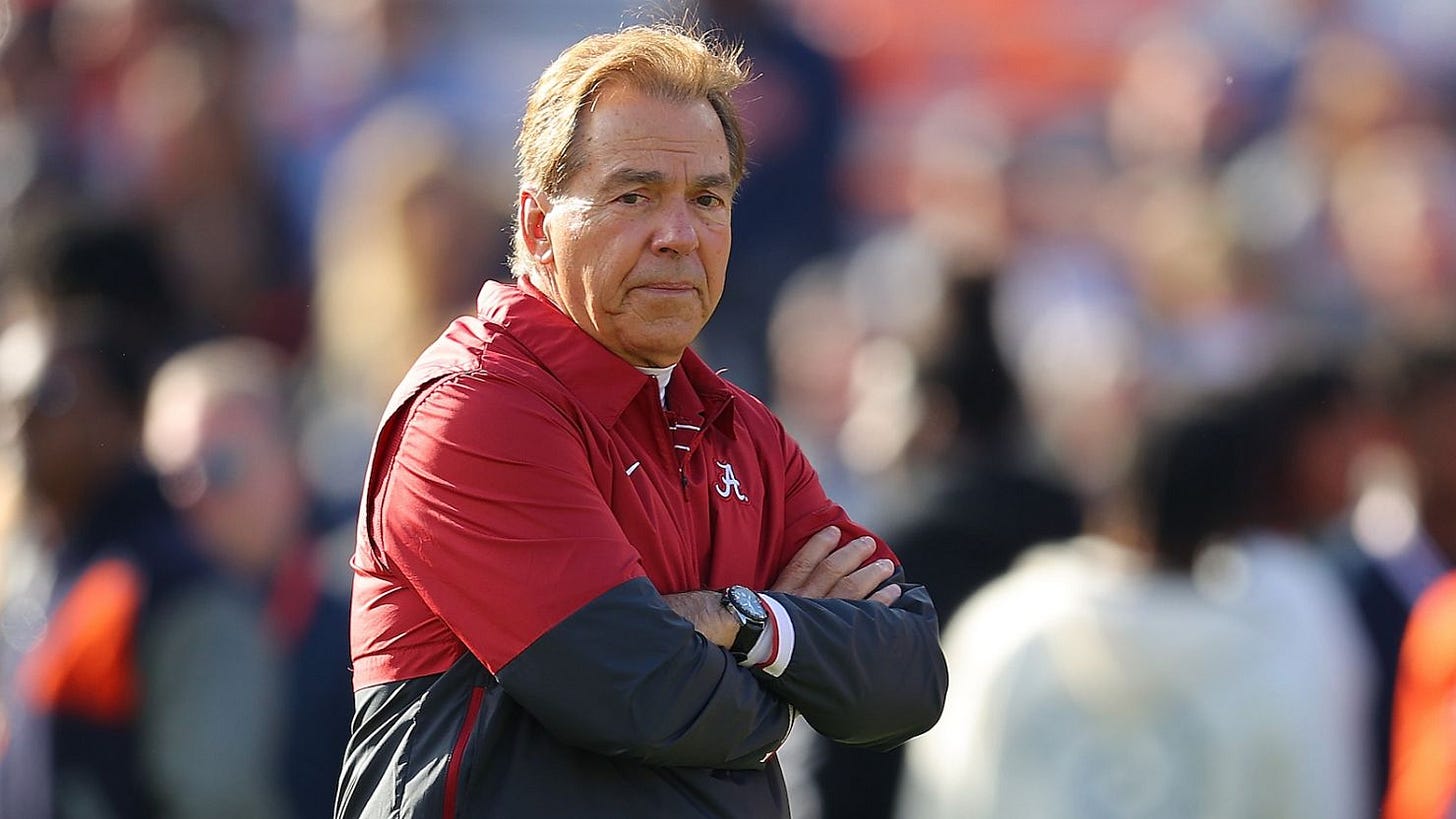

For the football buffs out there, this will all sound vaguely familiar. The legendary Nick Saban was on Hard Knocks last week to discuss transactional vs. transformational leadership. Transactional leadership is about if you do this, then I will do this. If you play well, I will praise you. Transactional leadership is results based. It is toxic, and it often leads to a decay in organizational culture.

Transformational leadership is a service mindset in which, as Saban so adeptly stated, “you are trying to help [others] for their benefit. You have a vision for what you want them to accomplish…and you are going to try to inspire them to help” accomplish that vision.

In that hug, my friend demonstrated transformational leadership. Luckily for me, he cared about me for no other reason than he was my friend. There were no strings attached; that hug wasn’t asking me to play better football next year. Instead, it said I am here for you, despite your inability to keep the ball out of the opponents’ hands. I am with you, and there is nothing you can do about it. In that hug, Chris taught me a lot about leadership. It has shaped how I approach team building and organizational culture development. It showed me first-hand the value of what service minded individuals can do for others and teams. It’s been ten years since that hug, but I still think about it often. That hug was a small act with a lot of impact in how I lead my life. If Nick Saban’s seven national championships are any indication, transformational leaders make champions. Who are you hugging today? Hug Like a Champion Today! #HLACT!

One Last Thing

The coming weeks will have more lessons from the boys of the Sprint Football team. So, to get everyone HYPED, here is a highlight video from back in the day where you can see that we had a fanbase the size of a small high school, but I think we played with some passion.

In the opening clip, you will see #83 Justin Zemser, a person I look to every week for how to be a better person. You will Joe Taylor, the man who held me as I cried the year before and remains the best leader I ever worked for. You will see a crowd of boys that became a group of men I am eternally grateful to know.